Introduction

The word 'prostitute' comes from the Latin pro-stituere, meaning 'to publicly exhibit'. It suggests that someone is put on public display, like a commodity in a shop window, to be examined and sold to anyone who is willing to pay the price. In other words, the word describes quite well what prostitution is all about. In prostitution, not only the body, but the entire human dignity is for sale.

Talita meets women who have been trafficked, but we also meet women in prostitution who have not been transported within or between countries, but who have nevertheless been treated as commodities. Other people, because they can pay for it, have considered themselves entitled to treat them as they please. They have bought access to another person's body to satisfy their own desires. This is not a relationship between equal parties entering into a relationship on equal terms, but a commercial exchange where two parties have different conditions and are in different situations.

Author Kajsa Ekis Ekman describes it as follows:

“The fragmented self is a reaction to a sexuality that is the antithesis of what voluntary and mutual sexuality is. Voluntary and mutual sexuality is about actually connecting with another person, opening yourself up in some way. It is an intimate situation where you give yourself over. You experience something together with someone else. When it comes to bought and sold sex, it's about two people who are in completely different situations. One person enjoys it and the other person doesn't enjoy it at all. The other person is only there because they have to, because they need the money. They often feel disgust and don't want to be there at all. They deal with it by somehow shutting down. So, if sexuality is usually about giving yourself over to the moment, this is the opposite, where you shut down. When you shut down, you can use a variety of strategies, and this is something that is documented in testimonies from people in prostitution. For example, you try to think about something else, take on a different name, or keep track of time. You do a lot of different things to avoid feeling and thinking about what you are going through."

In Sweden, it is illegal to buy sex, but not to sell your body. This is because, after many years of research, we have come to understand that the person who suffers in prostitution is the one selling themselves (usually a woman), and she therefore needs all the support she can get to leave the sex trade. The buyer, on the other hand (usually a man), uses the woman as a commodity, which is completely unacceptable in an equal society. Who is she who sells her body?

She is the young mother from a southern European country.

She is the girl sitting in the rain crying, who has cramps.

She is the woman who cannot stop washing herself and whose body is covered in sores.

The girl who doesn't dare go to the swimming pool on her own for fear of being bullied

Several authorities and organizations report that the proportion of children and young people who are exploited in the sex trade and who seek help at reception centers has increased in recent years. Among other things, adults seek out children and young people for sexual purposes via, for example, gaming apps or social media platforms such as Tinder, Instagram, Snapchat, Grindr, Badoo, TikTok, KiK, and Onlyfans. The number of reported crimes involving the purchase of sexual acts from children is also increasing. In 2019, 224 crimes were reported, compared to 131 reported crimes the year before. Unaccompanied children and young people are also a particularly vulnerable group of migrants that has received attention in recent years.

Online, sugar dating is marketed as an opportunity for young people to meet older individuals who are willing to pay for their joint vacations and restaurant visits. In reality, it is often a disguised form of prostitution, where the sex buyer attempts to circumvent the sex purchase law. The fact that sugar dating is a growing problem is evident not least in police investigations. The number of unreported cases is said to be high, and the way the police prioritize their resources is crucial to getting to the sex buyers. This is according to police inspector Simon Häggström, who has been working to combat prostitution and human trafficking for many years.

There is a strong connection between how well you realize your own value as a human being and what you are prepared to expose yourself to. We are not saying that there are no women who have chosen a life of prostitution, but we have never come into contact with anyone who – after we got to know her more than just superficially – said that she felt good about prostitution. On the contrary, it often turns out that in order to cope at all, women unconsciously dissociate, i.e., shut themselves off from their experiences or (in the worst cases) split their personalities into different parts. We fight for the equal value of all people and therefore refuse to accept that there are people who exploit the fact that some people are not aware of their own value.

The path into prostitution

Push factors

The most important reason why women end up in prostitution and are exploited in the most ruthless way is undoubtedly the fact that there is a demand among men to buy another person's body. Without demand, there would be no market. That said, there are two other factors that often contribute to a woman being drawn into prostitution: sexual abuse and poverty. Depending on which country the vulnerable woman comes from and which social class she belongs to, these factors affect her to varying degrees.

Women from countries outside Europe, such as Nigeria, have often come to Sweden in circumstances resembling human trafficking. Poverty is the main reason why they have accepted offers of work in Europe. They may have a history of sexual abuse, but this is not described as the main reason why they have ended up in prostitution in Sweden. It is the dream of a better life that makes them willing to take greater risks than someone who has food on the table and a roof over their head.

Women from countries in southern and eastern Europe, such as Romania, also report poverty and early sexual trauma, but unlike third-country nationals, they describe both push factors as being of roughly equal importance. Poverty is not as extreme and widespread as in some countries outside Europe, but almost all of them come from economically and socially disadvantaged areas in their countries and they can testify to early sexual trauma that has given them a feeling of being worthless and used up.

Women who have lived all or most of their lives in Sweden often have a different story. Sexual abuse is the main reason they got involved in sex work, while the need for money is described as what pushed them over the edge. Below, we explore why the link between sexual abuse and prostitution is so strong.

External and internal coercion

It is obvious to most people that external factors can force a person into prostitution, such as threats from a pimp or poverty, but it can be more difficult to understand the "internal compulsion" that many struggle with, which is often the result of early sexual abuse.

Through all our meetings with hundreds of women in prostitution, it has become clear to us that there is a very strong link between prostitution and early sexual trauma. Research also supports this conclusion. One could say that the abuse creates an inner compulsion that leads to prostitution and is rooted in, among other things, a damaged self-image, shame, anxiety, and an unconscious desire to regain control.

Many have described this inner compulsion as a restlessness that grows and grows until one acts on it. It drives them like an "inner pimp," controlling the deeply traumatized individual and ensuring that she puts herself in a situation where the abuse is repeated. Being sexually abused at a young age fundamentally affects a person's view of themselves and the world around them, making them extremely vulnerable to further abuse and manipulation.

The following quote, from the book Transforming Trauma – A Guide to Understanding and Treating Adult Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse written by Anna C. Salter, says a lot about the vulnerability of a person who has been abused as a child and how ruthless people, such as the pimp in this case, are prepared to exploit it:

"Beauty? Yes. Sexual experience? To some extent. But it's easier to learn than you think. What's more important than anything else is obedience. And how do you get obedience? You get obedience if you get women who have had sex with their fathers, their uncles, their brothers—you know, someone they love and are afraid of losing, whom they don't dare defy. Then you just have to be kinder to the women than they've ever been—and more dangerous. They'll do anything to please you. That's how it works." He nods to the women and they both smile. "Both of these girls have been with their fathers. Now they're making me rich—and they're happy."

Emotional shutdown and dissociation

Emotions are something that absolutely must not exist in prostitution. On the contrary, one of the prerequisites for a woman – who does not abuse drugs or alcohol – to be able to endure the degradation of prostitution is that she is able to shut off all emotions and disappear mentally. Researchers Sven-Axel Månsson and Ulla-Karin Hedin argue that sexual abuse during childhood has a greater impact than anything else on whether a person ends up in prostitution later in life. They explain a woman's entry into prostitution using a so-called direct effect model. The model states that sexual abuse in childhood increases the risk of prostitution later in life, regardless of whether there are other contributing factors. It can be said that repeated sexual abuse leads to early training in emotional shutdown and dissociation as soon as the person comes into contact with anything related to sex.

Dissociation is a well-known phenomenon in psychology. When a person is exposed to severe stress, such as a threat to their life, many different things happen in the body. The amount of stress hormone in the blood increases significantly, the heart begins to beat faster, and the brain makes a split-second decision about whether it is best for the individual to flee or fight. If the brain interprets the situation as impossible to escape or fight, the person ends up in a state that can be described as a freeze reaction. The threatening event is then too overwhelming and difficult for the psyche to handle, resulting in a kind of mental escape instead of a physical one. This mental escape is called dissociation and is a survival mechanism. Some experience it as looking down on themselves from a place on the ceiling, others as disappearing into themselves or away to a distant place.

In a traumatic situation, when a person dissociates, the body registers what is happening to it even though the person does not feel present. The body remains in the situation and therefore carries memories of feelings, touch, pain, and violence. These bodily memories remain, but the context is lost. She may even find it difficult later in life to understand the story her body is telling.

Through dissociation, the brain shuts down thoughts, feelings, and impressions in order to survive, thereby splitting identity and memory into different parts that deal with different aspects of the traumatic event. As the author of the book Relation och trauma (Relationship and Trauma), Karin Persson, so aptly describes it:

"The child fled and left her body to the perpetrator. Where was the child/woman while her body was being violated? Sometimes she was there, a little way off, registering what was happening. Sometimes she was in another country, in another time, in another child. In a fantasy world where she knew all the circumstances. Sometimes she was nowhere. Nothing existed. What is felt is one thing, what happens is another, what happens is not entirely without being divided into small fragments, what happens is not now, perhaps later or never."

As a psychological defense mechanism, dissociation is an ingenious psychological solution, as it enables the traumatized person to actually survive the difficult situation. However, sometimes a person continues to dissociate unconsciously long after the acute, threatening situation has ended. This can happen, for example, in a stressful situation where events in the present bring back difficult memories, but unlike when the traumatic event actually took place, the mental escape now serves no positive function. Dissociating, and thus not being emotionally aware of who you are or what you are experiencing, can instead lead to consciously or unconsciously exposing yourself to new dangerous events that further hinder healing and reinforce a negative self-image.

Many people who have been subjected to repeated sexual abuse as children say that later in life, when they found themselves in financial crisis and ended up in prostitution, they were able to endure it because they "automatically shut down" during encounters with sex buyers. They describe it as being mentally and emotionally absent and, during the abuse, completely disconnected from themselves and their bodies.

Unhealthy shame

Early sexual abuse leads to a number of different consequences for the victim. In addition to early training in emotional shutdown and dissociation, several of the consequences contribute to vulnerability, which in turn increases the risk of ending up in prostitution. One such consequence of abuse is shame.

Shame is a feeling that can be both healthy and unhealthy. Healthy shame, like all basic emotions, serves a purpose in humans. It prevents us from violating the boundaries of others. Unhealthy shame, on the other hand, is a deep feeling of being worthless and insignificant as a person. A pervasive feeling of shame is rooted in the belief that one is not a full-fledged human being.

People who have been sexually abused as children often experience this deep emotional pain in their lives: a pain that often includes a strong aversion to their own bodies. A recurring explanation that women themselves give for why they ended up in prostitution is that they do not believe they deserve anything better. In their own eyes, they are "used up," "disgusting," "dirty," and "worthless," and have been so ever since they were abused as children. Being treated as a commodity in adulthood is nothing they react to particularly strongly. On the contrary, it fits in quite well with their damaged self-image.

The world is hostile

According to some researchers, the perception that the world is hostile is a long-term consequence of sexual abuse. The significance of this is that individuals who have been sexually abused tend to view the world as a hostile place where nothing is naturally deserved and nothing is given "freely and for nothing." The only way to get something is to offer something in return or to trick someone into giving it to them. The reason for this view is that those who were sexually traumatized as children learned that their bodies were their most valuable asset in the eyes of certain significant adults. It is not uncommon for prostitution to be described as a logical continuation of having "sold sex" at home. Many exploited women make a decision that if they have to have sex with men anyway, they might as well make sure they get paid for it.

Anxiety regulation

Childhood abuse can also lead to a kind of "learned helplessness." It doesn't matter what the child does (or doesn't do) to avoid the abuse—it doesn't stop anyway. The knowledge that "something will happen, I don't know when, but I know it will" creates a lot of anxiety. For some children, the only relief they ever feel is the relief that comes immediately after an abuse has taken place. That is when it is most likely that they will be left alone for a while. Growing up with this feeling of constant fear and learned helplessness is unbearable for many. Many struggle with fear and anxiety long after the abuse has stopped. Putting oneself in situations where one is exposed to new abuse can be a way of controlling the anxiety, which is usually least intrusive immediately after an abuse.

Regain power and control

There is also research indicating that prostitution is sometimes a way of repeating early traumatic experiences in a subconscious attempt to change the painful experience and thus heal a damaged self-image. It is very common for people who have been sexually abused to relive the event or events in flashbacks and nightmares, but the abuse can also be relived in concrete, new events. The goal is—consciously or subconsciously—to regain power and control, but tragically, this instead leads to revictimization, meaning that the person once again becomes a victim of abuse, and in the long term, a condition that some experts call psychological paralysis.

Problems with boundaries

Another important reason why people who have been subjected to early sexual abuse are particularly vulnerable to sexual exploitation later in life is the problem of boundaries. Being subjected to sexual abuse as a child leads to confusion about one's own boundaries. Significant adults have treated the child as if she has no right to her own body, and that message lives on within her into adulthood. Many women in prostitution talk about intrusive men they encounter in their everyday lives, for example in cafés or on the subway, who suggest that they want to have sex with them. Because the woman has not been taught that her “no” means anything, the stranger manages to get his way. These same women see their inability to reject strangers as a very big problem. They feel that there is something fundamentally wrong with them. One woman said, “It feels like it says ‘prostitute’ on my forehead!”

Money – the only security

During the years we have worked with women in prostitution, we have not met a single person who, despite feeling good and having alternatives in life, has chosen to sell their body solely to earn extra money. However, this is often how prostitution is described in the media. On the other hand, we believe that money undoubtedly plays a major role for many women who take the step into prostitution. The experience of being completely left to one's own devices, without a single person close by to turn to when things get tough, is shared by many. What they lack is a sense of security and safety in life. Money can then become an alternative source of security and comfort. Seeking help from social services—if that is even possible—is unthinkable for many. In some cases, this is due to previous bad experiences, in others because of the difficulty of trusting others or simply because they do not feel they deserve any help.

Voluntary and involuntary prostitution

Those who defend prostitution argue that a distinction should be made between voluntary and non-voluntary prostitution, but we believe that such a distinction is irrelevant. The reason is, first and foremost, that in most cases it is impossible for a sex buyer to assess whether the woman is there "voluntarily" or not, as the majority of women in prostitution smile and are welcoming to everyone. A very small proportion show friendliness because they are there voluntarily. Instead, they are welcoming because they need the money, or are afraid that someone they love will be harmed by pimps and human traffickers if they are not sufficiently accommodating. Another reason why the distinction is not relevant is precisely the phenomenon of the "inner pimp" that we described above. Finally, regardless of whether she is there voluntarily or not, research shows that prostitution is harmful in several ways. The women are exposed to physical, psychological, and sexual violence, many develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and it has been shown that people in prostitution do not live as long as the average person in the population.

The way out of prostitution

Det finns många utmaningar för den som vill lämna sexhandeln. Förutom den uppenbara utmaningen som handlar om att skydda sig från hallickar och andra som ser en som en inkomstkälla och därför vill en illa när man lämnar, finns en rad olika hinder man ska ta sig över om man vill skapa ett normalt liv.

När våra kvinnor väl fattat beslutet att satsa allt på ett kort måste de övervinna svårigheten att lita på andra människor. Det kan ta lång tid att bygga upp förmågan till tillit igen, om den raserats tidigt i livet. För det första måste man lära sig identifiera och respektera sina egna gränser, för att därefter komma till insikt om vilka människor man faktiskt kan och bör lita på och vilka som inte är värda ens förtroende. En förutsättning för hela denna process är att man sakta men säkert har börjat inse sitt värde – att man är en person värd att älskas och respekteras.

Den som vill lämna ett liv i sexindustrin måste även vara beredd att jobba hårt med sin självkänsla – en del känner till och med att de behöver bygga upp en helt ny identitet. De behöver hitta svar på frågor som ”Vem är jag utanför prostitutionen?” och ”Vad kommer min familj tänka om mig om jag slutar skicka hem pengar?” De behöver även möta och bearbeta alla mörka minnen och känslor de begravt under lång tid, något som kräver både mod och envishet, samt komma till insikt om att det som hänt inte var deras fel. Allt detta kräver en djupdykning inom det egna jaget som kan vara smärtsam, men som på sikt leder till ny kraft.

En annan utmaning kvinnorna ställs inför när de lämnar sexhandeln är behovet av att hitta ett nytt sätt att överleva och försörja sig. De behöver även finna nya sociala sammanhang där de känner sig accepterade och kan vara sig själva.

Parallellt med allt detta måste vi, tillsammans med personen det gäller, komma fram till var – rent geografiskt – hon har störst möjligheter att lyckas. Hon kanske vill stanna i Sverige och ingå i vårt program, men har barn i hemlandet eller släktingar som är beroende av henne. Eller så har hon kanske extremt liten chans att beviljas uppehållstillstånd i Sverige – antingen som flykting eller via arbetstillstånd – och därför tvingas återvända till hemlandet. Då gäller det att skapa förutsättningar för ett tryggt återvändande och stöd.

För många av våra klienter, med ursprung i länder utanför EU, är Sverige inte det första land de kom till i Europa. Ofta är det första landet de anlände till Italien eller Spanien, dit människohandlarna inte sällan tagit dem via en mardrömslik resa i gummibåt över Medelhavet. Den vanliga rutinen är att alla migranter blir fotade direkt efter ankomsten och får lämna fingeravtryck, varefter de placeras på en flyktingförläggning alternativt att den kriminella ligan (som vill förhindra att myndigheterna får inflytande över personen) själva ordnar med husrum åt dem och genast börjar exploatera dem i exempelvis prostitution. Det faktum att kvinnorna som utnyttjas i prostitution ofta har lämnat fingeravtryck i ett annat land innan de kommer till Sverige, innebär att de enligt den så kallade Dublinförordningen ska skickas tillbaka dit för att söka asyl. De har inte rätt att söka uppehållstillstånd här. Dublinförordningen är en europeisk förordning som reglerar vilken medlemsstat som är ansvarig för att pröva en asylansökan inom EU. Om kvinnan däremot beviljas ett tillfälligt uppehållstillstånd (så kallat TUT), så ”faller Dublin”, det vill säga förordningen behöver inte tillämpas och personen kan stanna och söka asyl här efter att det tillfälliga uppehållstillståndet gått ut, vilket vanligtvis sker efter sex månader. Vi har vid några tillfällen under årens lopp stått vid en kvinnas sida som fått beskedet att hon ska överföras till ett annat europeiskt land med hänvisning till Dublinförordningen och vid varje tillfälle har kvinnan brutit ihop av förtvivlan och rädsla för att människohandlarna som finns där ska hitta henne och straffa henne för att hon flytt från deras kontroll.

Oavsett var kvinnan kommer bo är vårt mål att hon ska bli rehabiliterad och fullt ut integrerad i samhället. Hon ska känna sig empowered samt ha en försörjning och en bostad. Detta kräver flexibla lösningar. En av Talitas största styrkor är förmodligen just flexibilitet. Vi har exempelvis, vid mer än ett tillfälle, varit med om att forma en plan som går helt utanför våra vanliga ramar.

Som exempelvis när Olga från Moldavien, som kom till oss slussad av polisen 2017, vädjade om att få ingå i programmet i Sverige trots att hon inte hade någon som helst chans att få asyl. Hon hade släktingar att försörja i hemlandet men utsikterna att få jobb där var extremt små, dels på grund av fattigdomen i landet, dels eftersom hon tillhörde en etnisk minoritetsgrupp som var allmänt illa ansedd. Vi förstod att Olgas enda chans till ett drägligt liv utan prostitution var att få arbetstillstånd i Sverige – för arbeta hårt, det kunde hon. Vi lyckades hitta en lämplig arbetsgivare åt Olga, hon kunde då återvända hem och söka arbetstillstånd därifrån, och några månader senare var hon tillbaka i Sverige och kunde börja jobba.

Vanligtvis när en kvinna ingår i Talitas program är hennes första prioritet att delta i programmets obligatoriska delar: samtalsterapi, undervisning och framtidsplanering. Det är först i slutet av det första året och under hela andra året som fokus läggs på arbete och studier. Men för Olga, och många andra kvinnor i hennes situation, blir det absolut viktigaste att hitta en anställning i Sverige som i sin tur kan leda till trygghet.

Den vanligaste anledningen till att en person vill återvända till sitt hemland är att hon har barn som är kvar där. Även då krävs ett stort mått av flexibilitet från Talitas sida. För att bara förlita sig på återvändandeprogrammet, som i dagsläget drivs av jämställdhetsmyndigheten och IOM, har under årens lopp visat sig ohållbart.

Återvändandeprogrammet kan ge individen ett ekonomiskt tillskott under ett antal månader, men ibland behövs mer omfattande stöd under en lång tid. En del kvinnor som kommer till oss har stora skulder som tvingat dem in i sexhandeln. Därför, om vi menar allvar med att vilja hjälpa kvinnan ”hela vägen i mål”, måste vi vara beredda på att reda ut en hel del snåriga och komplexa situationer.

Slutligen finns givetvis mer specifika hinder och utmaningar för olika individer och grupper av kvinnor. Ett sådant exempel är rädslan för jujun bland de nigerianska kvinnorna. Det är en enorm utmaning att övervinna den rädsla de känner, såväl för människohandlarna och deras konkreta hämndaktioner som för de gudar som medicinmännen åkallat under jujuritualerna. Syftet med ritualerna de genomgått före avresan till Europa är att, genom hot om sjukdom och död, binda kvinnan i fruktan för vad som kommer hända om hon slutar betala av på sin skuld, flyr från människohandlarna eller avslöjar för polis eller andra utomstående vad hon varit med om.

Eftersom Talita vilar på kristen grund har vi när det gäller att hjälpa kvinnan att hantera och slutligen övervinna sin rädsla för jujun en fördel jämfört med andra aktörer i samhället. Vi kan nämligen lugna kvinnan genom att berätta att vi tror på Bibelns Gud, precis som hon gör, och påminna henne om att universums skapare har mer makt än de naturgudar som medicinmannen åkallat. Vid flera tillfällen har vi, genom att be tillsammans med kvinnan, lyckats övertyga henne om att hon är fri från förbannelsen och har rätt att göra vad hon vill med sitt liv.

The Sex Purchase Act

Excerpt from True Stories About the Path Out of Prostitution by Anna Sander and Josephine Appelqvist

It was 1998, the year before the Sex Purchase Act came into force, and heated discussions were taking place in parliament and the media about whether the new proposal to ban the purchase but not the sale of sexual services was good or bad. One Friday evening in February, a TV crew from Germany squeezed themselves and all their equipment into the bus, which was parked outside the parish hall in Stadshagen on Kungsholmen in Stockholm and was being filled with thermos flasks, sandwiches, and supplies for the night. The TV crew, consisting of two cameramen and a journalist, listened intently and with great curiosity to our opinions on the new controversial bill. We thought the bill was a bad idea and explained that nothing should jeopardize the opportunity we now had to actually meet the women and tell them that there was a way out of the misery they found themselves in. Of course, we wanted the pimps to be caught—and preferably locked up for good—but the risk was too great that the trade would go underground.

The journalist nodded understandingly but did not seem entirely satisfied. He continued to ask questions and said that others he had spoken to in Sweden who advocated a law against buying sex claimed that the sex trade would not necessarily go underground and that, even if it did, the positive effects of criminalizing the purchase of sex would still outweigh the negative ones. The German journalist was obviously well-read and had interviewed several Swedish politicians and activists. His questions sowed seeds of doubt in us, doubts that grew stronger in the months following the entry into force of the sex purchase law. We realized that we had not thought through the issue as carefully as it deserved—we had not even asked the women what they thought about the bill.

Once we started doing that, a completely different picture emerged. The women were overwhelmingly positive about the law and did not see it as a threat, but rather as a security, something they could lean on if they wanted to seek help from society. If lawmakers decided that buying sex was a crime, the authorities would have to come up with a solution for those who sold it. That was roughly how they reasoned. We understood them, and step by step our attitude toward the sex purchase law changed until one day it was diametrically opposed. To our great disappointment, however, the large package of support measures in the form of rehabilitation that one might have expected society to provide when the new ban was introduced failed to materialize. Instead, one politician after another gave interviews on television, walking along Malmskillnadsgatan. They proudly showed off the deserted street, but no one seemed to wonder what had happened to the women.

On January 1, 1999, it became illegal to buy sex in Sweden, and prostitution on Malmskillnadsgatan declined quite immediately after that, but it did not go underground in the way we initially feared it would. We had no problem reaching out to the women, as those who already knew about the bus continued to come there. The women told us that they were not afraid to move around the area around Malmskillnadsgatan because they were not doing anything criminal. But when the number of clients decreased, the number of women in prostitution naturally decreased as well. The trade in human bodies had been curbed thanks to the new law, and virtually the entire Swedish society was positive about the change. The more we read and the more experience we gained, the more we understood how obvious the Sex Purchase Act is in an equal society.

Today, we cannot imagine Sweden without it, and almost all the women we have met over the years are grateful that the law exists and that society is on their side. This is what one client once said to us: He [the sex buyer] had various forms of power over me—physical, psychological, financial, and social. The only weapon I had was the Sex Purchase Act. I knew that if I called the police, they would be on my side, not his.

A historical review

The decision to introduce a ban on the purchase of sexual services was not taken overnight. On the contrary, it was the result of over 30 years of solid research in the field of prostitution – research that is exceptional in many respects because it is based on what people in prostitution have said. The starting point was the 1977 prostitution inquiry, which remains the most comprehensive survey of prostitution ever conducted in Sweden. Kajsa Ekis Ekman writes the following in her book Varat och Varan (Being and Commodity):

When the Prostitution Inquiry was launched in 1977, the experts did something that was unusual for government inquiries both then and now: they spent three years in the prostitution milieu. They left their desks and traveled around to sex clubs throughout Sweden, interviewing prostitutes, sex buyers, and others involved in the environment. They wanted not only to map the spread of prostitution, but to understand what prostitution was. The result was an 800-page report, 140 pages of which consist of people's own stories. Page after page, prostituted women told about their upbringing, their path into prostitution, the sex buyers: family men, executives, criminals; the role of alcohol and drugs, different types of pimp relationships, how prostitution affected them,256 violence, shame, strength, and survival strategies. This was something unique. Previously, research had focused on prostitutes as deviants. By labeling them as deviants, prostitution was written out of society. Now, stories from the world of prostitution formed the basis for a completely new analysis, in which prostitution was instead explained as a concentrated, extreme variant of the relationship between the sexes in general.

The report Prostitution in Sweden, Background and Measures, which was presented after the investigation, proposed that prostitution should continue to be decriminalized, but emphasized the importance of other social and legal solutions to reduce it. In 1993, a new investigation into prostitution was conducted, and in the report Sex Trade, the investigator proposed that prostitution should be criminalized by introducing a ban on both the purchase and sale of sexual services. The investigation considered that criminalizing prostitution was a necessary step to make it clear that prostitution as a phenomenon is not accepted by society. The investigation's proposal was met with widespread criticism and was not implemented.

The proposal that ultimately led to the introduction of the Sex Purchase Act was the so-called Kvinnofridspropositionen (Women's Peace Proposal), which proposed a large number of different measures in various sectors of society to combat violence against women, prostitution, and sexual harassment in the workplace. The most important insight regarding the issue of prostitution was that attention must be focused on the buyers. Without demand, there would simply be no prostitution. The fact that those who sell sex are in a very vulnerable situation was cited as the main reason for criminalizing only the buyer. The government considered that it was not reasonable to also criminalize those who, at least in most cases, are the weaker party and are exploited by others. The importance of motivating women to seek help to escape prostitution was also emphasized, so that they would not feel that they risked any form of punishment.

Those who defend prostitution argue that a distinction should be made between voluntary and involuntary prostitution. However, from a gender equality and human rights perspective, and with the focus shifted from supply to demand (human traffickers, pimps, and sex buyers), the distinction between voluntary and involuntary prostitution becomes irrelevant.

The Sex Purchase Act is unique in its kind and a very useful tool for tackling human traffickers, pimps, and sex buyers. We can be proud of the police officers who fight sex trafficking with tenacity and great commitment. Without prostitution units within the police force that intervene against sex buyers, carry out identity checks, meet with informants, help those at risk, collaborate with social services, and are constantly present in prostitution environments, the law is reduced to nothing more than a piece of paper.

However, enforcement of the ban in society depends largely on the priorities set by the police and the resources at their disposal. According to both police officers and prosecutors, significantly more sex buyers could be prosecuted if the crime were given higher priority. One reason why sex purchase crimes are not prioritized is the low penalty value of the crime. For many years, the penalty scale for purchasing sexual services was a fine or imprisonment for a maximum of one year. In the summer of 2022, fines were removed from the scale of penalties, and since then the penalty has been imprisonment for a maximum of one year. Anyone who purchases sex from a child between the ages of 15 and 18 is convicted of the crime of exploitation of children through the purchase of sexual acts and sentenced to imprisonment for a maximum of four years.

Anyone who purchases and sexually exploits a child under the age of 15 is convicted of child rape and sentenced to imprisonment for a minimum of two and a maximum of six years. After the Supreme Court examined the issue of sentencing for purchasing sexual services in 2001, more than 85 percent of all prosecutions for a single purchase of sexual services have resulted in a penalty of 50 daily fines. Not once in 23 years has the penalty for purchasing sex (from an adult) been anything other than a fine, and only on a few occasions have perpetrators been sentenced to prison for exploiting children through the purchase of sexual acts. Many have reacted to the low penalties, and in July 2020, Minister of Justice and Migration Morgan Johansson gave an additional assignment to the ongoing sexual crimes investigation aimed at removing fines from the scale of penalties for purchasing sexual services. In the summer of 2022, the Riksdag decided in accordance with the investigation's proposal.

Initially, the ban on purchasing sexual services was included in a separate law, which became known colloquially as the "sex purchase law." Today, the ban is included in Chapter 6, Section 11 of the Swedish Penal Code and reads as follows:

"Anyone who, in circumstances other than those referred to earlier in this chapter, engages in a temporary sexual relationship in exchange for payment shall be sentenced for purchasing sexual services to a fine or imprisonment for a maximum of one year. The provisions of the first paragraph shall also apply if the payment has been promised or given by another person."

The compensationmay be financial or of another kind, such as payment in alcohol or drugs. It may be provided in advance or in connection with the sexual service being performed. For liability to arise, it is sufficient that compensation has been promised, so that payment is a prerequisite for the sexual service.

In 2010, under the leadership of Anna Skarhed, an official evaluation of the ban on purchasing sexual services was conducted. The evaluation showed, among other things, that the ban had a deterrent effect on prospective buyers of sexual services, that street prostitution had been halved, and that Sweden was considered an unattractive market for human trafficking.

Prostitution is not a "job" but a form of violence against women and children by men. This is the view that we in our country – regardless of the government – have actively advocated since the purchase of sexual services was criminalized. However, because legislation has so far used the term "sexual service" to describe the trade in women's bodies, this has created consequential problems. The term "sexual service" indicates that it is a matter of exchanging money for a service between two equal parties. One example of the terrible consequences of this is the Swedish Tax Agency's treatment of people in prostitution. During the summer and fall of 2023, Talita came into contact with several women who were being pursued by the authorities for unpaid taxes, on the grounds that prostitution is a "job" that should be taxed.

Fortunately, on November 21, 2023, a proposal for stronger criminal law protection and the removal of the concept of sexual services was presented in report SOU 2023:80. In a subsequent bill (2024/25:124), the government followed the inquiry's line and proposed a change in the classification of the offense from "purchase of sexual services" to "purchase of sexual acts." The change came into force on July 1, 2025.

The Sex Purchase Act was also extended to cover certain acts that take place digitally.

Ban on digital sex purchases

On July 1, 2025, an extension of Chapter 6, Sections 11 and 12 of the Swedish Penal Code, i.e., the purchase of sexual acts and procuring, came into force. The extension means that criminal liability also applies to the purchase of sexual acts and procuring carried out remotely. It can be said that, with this change in the law, Sweden is criminalizing a certain type of pornography production, but the prerequisite for a person who pays for pornographic images and films to be convicted of a crime is that there is a causal link. The perpetrator must have persuaded the other person to perform or tolerate a sexual act in exchange for payment. In other words, "ordinary" pornography falls outside the scope of application, since the purpose of such production is not to show a sexual act only to the person who pays, but rather to "create a depiction that is to be made available to the public in some way" (quote taken from the report SOU 2023:80).

In its response to the inquiry (SOU 2023:80) that preceded the bill, Lund University pointed out that the legislation risked being inconsistent with regard to the criminalization of sexual acts in exchange for payment. They wrote the following: "The proposal would mean that a certain type of pornography production—digital pornography made to order—would be criminalized, while it is difficult to see that this particular type of production would be more harmful than other types of sex for remuneration that are currently permitted, such as the production of pornography." (source: Lund University, Dnr V2023/3116 p. 4.).

The Jönköping District Court was also hesitant in its response: "The expansion of Section 11 further blurs the line between what is criminalized, such as the purchase of sexual acts, and what is protected by the constitution in the form of pornography production. A question for the legislator is how much broader the criminalized area can become before there is reason to review the constitutional protection of pornography production." (source: Jönköping District Court, Dnr Ju2023/02590 p. 2.)

The investigation discussed whether the proposed extension would infringe on freedom of expression, and the conclusion reached was that this would not be the case. The reasoning was that criminalization does not target the image material itself, which could still be possessed and distributed. Instead, the criminalisation focuses on how the material is obtained. The extension of criminal liability for the purchase of sexual acts and procuring to also apply to remote transactions thus meant that the method of acquisition was criminalised, which does not conflict with the constitution.

In Talita's response to the investigation, we stated the following:

Talita's solid experience in offering support to women in prostitution, in all its forms, has clearly shown that commercial pornography cannot be distinguished from other types of prostitution. It is documented prostitution where sexual acts are performed in exchange for payment, with the difference that a camera documents the purchase of sex. Our research and experience show that the path into pornography is often the same as into prostitution, characterized by abuse, poverty, and psychosocial problems. The consequences of prostitution are deeply serious for those affected, regardless of whether it takes place in front of a camera or not, and include PTSD, chronic illness, dissociation, and more. However, the trauma that arises when one's prostitution is documented and disseminated can be even more devastating, as the material becomes permanently available on the internet. These experiences are confirmed by both Swedish and international research, exemplified by the report "

Sexuellt utnyttjade i pornografiska syften" (The impact of pornography on victims of sexual exploitation for pornographic purposes), SOU 2023:98.

The latest research report, "Invisible Victims," produced by researchers at Marie Cederschiöld University College on behalf of the aforementioned investigation, concludes that the harm and seriousness of sexual acts in exchange for compensation are comparable, regardless of whether the acts are digital or physical. The study emphasizes the importance of treating sexual exploitation on digital platforms with the same seriousness as physical sex purchases, to ensure that all victims receive adequate protection.

We at Talita are grateful that the inquiry has identified and acknowledged this need. We welcome the proposals that clarify the definition of sex purchase and thereby broaden the scope of the Sex Purchase Act. Our research and practical experience support the conclusion that remote sex purchases have consequences comparable to those of physical sex purchases. In addition, the spread of documented prostitution online causes permanent damage because the material always remains available and victims fear being recognized and stigmatized.

The inquiry's proposal to extend the legal regulation of 'purchasing sexual services' to also include acts performed remotely is an important step in ensuring that society's protection, support, and care covers all victims of crime, regardless of where the crime was committed, whether the crime has been documented, and whether it has been disseminated. However, we strongly question the inquiry's distinction between what is referred to as 'traditional pornography production' and remote-based sex purchases. Our response to the consultation points out how this distinction favors the interests of porn producers over those of victims, even though producers have a dual role as both buyers and pimps, where they first pay for sexual acts and then make money from the documented sex purchase.

Exempting pornographic material produced for the general public, rather than for individual buyers, from criminal liability does not take into account the testimony of victims and survivors that the most traumatic aspect of their paid sexual acts being documented is precisely that it is disseminated to the general public. Furthermore, we question the proposal that subscriptions to sites such as OnlyFans should be exempt from criminal liability. We urge policymakers to critically reevaluate these conclusions and proposals to ensure that the Sex Purchase Act covers all types of paid sexual acts, that perpetrators are held accountable, and that all victims of sexual violence and exploitation receive the protection they need.

From an international perspective

Since the Sex Purchase Act was introduced in Sweden in 1999, it has gained significant international importance. The law—often referred to internationally as the Swedish Model, Nordic Model, Equality Model, Abolitionist Model, or Survivor Model—is based on a simple but crucial principle: responsibility should not be placed on the person being exploited, but on the person buying sex and those who profit from the vulnerability of others.

In the international debate, prostitution is sometimes described as "work" – sometimes as vulnerability. Those who understand that prostitution is vulnerability often point to the Swedish Sex Purchase Act as the most consistent legislative route to actually reducing demand and shifting blame and responsibility to the right side. It is described by many as the only legislative model that seriously tackles the driving force behind the sex trade: the buyer – and which at the same time is based on the principle that those who are exploited should be met with protection, support and ways out.

In recent decades, several countries have also been inspired by Sweden and chosen to introduce similar legislation, either in whole or in part, with a focus on demand (purchases). These are Norway (2009), Canada (2014), Northern Ireland (2015), France (2016), Ireland (2017), and Israel (2020). Norway has also criminalized the purchase of sex abroad (something that Sweden has not yet introduced), and France has built a clearer exit route into its legislation—with the right to support measures and ways out, where people in prostitution can get help through a special program.

In addition, discussions and legislative initiatives are underway in several countries where it has been recognized that legalization or far-reaching decriminalization does not protect those who are bought and sold. On the contrary, it makes sex buying more acceptable, increases demand, and causes the market to grow—resulting in more pimping and human trafficking.

At the same time, important discussions are also taking place at EU level. On September 14, 2023, the European Parliament adopted a resolution on the cross-border effects of prostitution and its links to gender equality and women's rights, focusing on demand and exploitation, and calling on EU member states to introduce the Equality Model/sex purchase law.

For such political steps to be possible – and followed up in practice – long-term advocacy work is required. International civil society plays a crucial role in this regard. Talita is a member of CAP International, which works at the European and global levels to promote the Equality Model/sex purchase law, strengthen the survivor perspective, and push for legislation and standards that reduce demand and build real pathways out of exploitation. CAP International also contributes to international forums and the UN system, including by participating in consultations, submitting written submissions, and making oral interventions – thereby helping to hold international bodies accountable for their commitments to women's and girls' rights.

Another important international voice in recent years is Reem Alsalem, the UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women and girls. In a thematic report to the UN Human Rights Council (2024), she describes prostitution as a system in which violence, exploitation, and unequal power are central—not "work." The report emphasizes that prostitution is linked to structural injustices such as poverty, racism, discrimination, sexual violence, and male demand – and that women and girls who end up in prostitution suffer devastating consequences for both their health and their life opportunities. Alsalem also advocates the Equality Model/sex purchase law: that buyers and actors who profit from the vulnerability of others are held accountable, while those who are exploited are provided with protection, support, and ways out. It is one of the clearest UN documents of its kind, clearly linking prostitution to violence and exploitation – and at the same time identifying demand as a key to change.

The sex buyer

Historical review

Sven-Axel Månsson is a Swedish sociologist and professor emeritus in social work (active at Lund, Gothenburg, and Malmö/Malmö University, among others). He is one of Sweden's most long-standing and influential researchers on prostitution, pornography, and sexual exploitation.

Månsson has played a decisive role in bringing sex buyers into the public eye. Among other things, he has investigated men's motives for buying access to women's bodies (Månsson, 1996a, 2002, 2004, 2008, 2010, 2015; Månsson et al., 1988; Månsson & Linders, 1984) and concluded that it is linked to the influence of patriarchy on sexuality. "There is a strong connection between men's motives for visiting a prostitute and the social learning process whereby boys become men..." (Månsson & Linders, 1984, p. 154).

Boys learn to dominate girls in sexual relationships, where the act of domination itself defines traditional male masculinity. As gender equality increases, some men reject women's rights advances and purchase sex to gain access to "the traditional gender order" and to "channel their aggression towards women" (Månsson, 2002, p. 145). Månsson's research among sex buyers debunks common myths, such as that only older men buy sex, or that many sex buyers are disabled and therefore cannot have sex outside of prostitution.

In-depth interviews with 66 sex buyers, conducted together with my colleague Anna Linders, showed that almost half (47%) had a female partner, that most (90%) were under 30 when they first bought sex, and that the majority (79%) had bought sex abroad on their most recent occasion (Månsson & Linders, 1984, pp. 73–86). They showed that sex buyers do not belong to any particular social category and that prostitution "is a collective male issue" (Månsson et al., 1988, p. 15).

As early as 1976, Månsson began to consider how the prostitution system could be abolished and realized that demand for prostitution must be limited. He wrote that "the buyers are, even more so than the pimps, a prerequisite for prostitution. If it is legally possible, should we not then prohibit the purchase of [sex]?” (Månsson & Larsson, 1976, p. 135).

Månsson became increasingly convinced of the need to criminalize the buyer when he began researching the global sex trade in the 1990s (Månsson, 1991; 1996b). He realized that social services and education aimed at sex buyers could not address the structural inequalities underlying the growing sex trade and men's demand for underprivileged foreign women. According to Månsson, this demand is based on racist and ethnic stereotypes (Månsson, 1995; 2002) and constitutes a "modern form of colonialism" (Månsson, 1992). Just like today's sex buyers, colonizers believed "that they had an obvious right to access colonized women in the same way that they appropriated land and raw materials. It is the same mentality that is expressed in today's sex industry exploitation of the Third World" (Månsson & Linders, 1984, pp. 86–87).

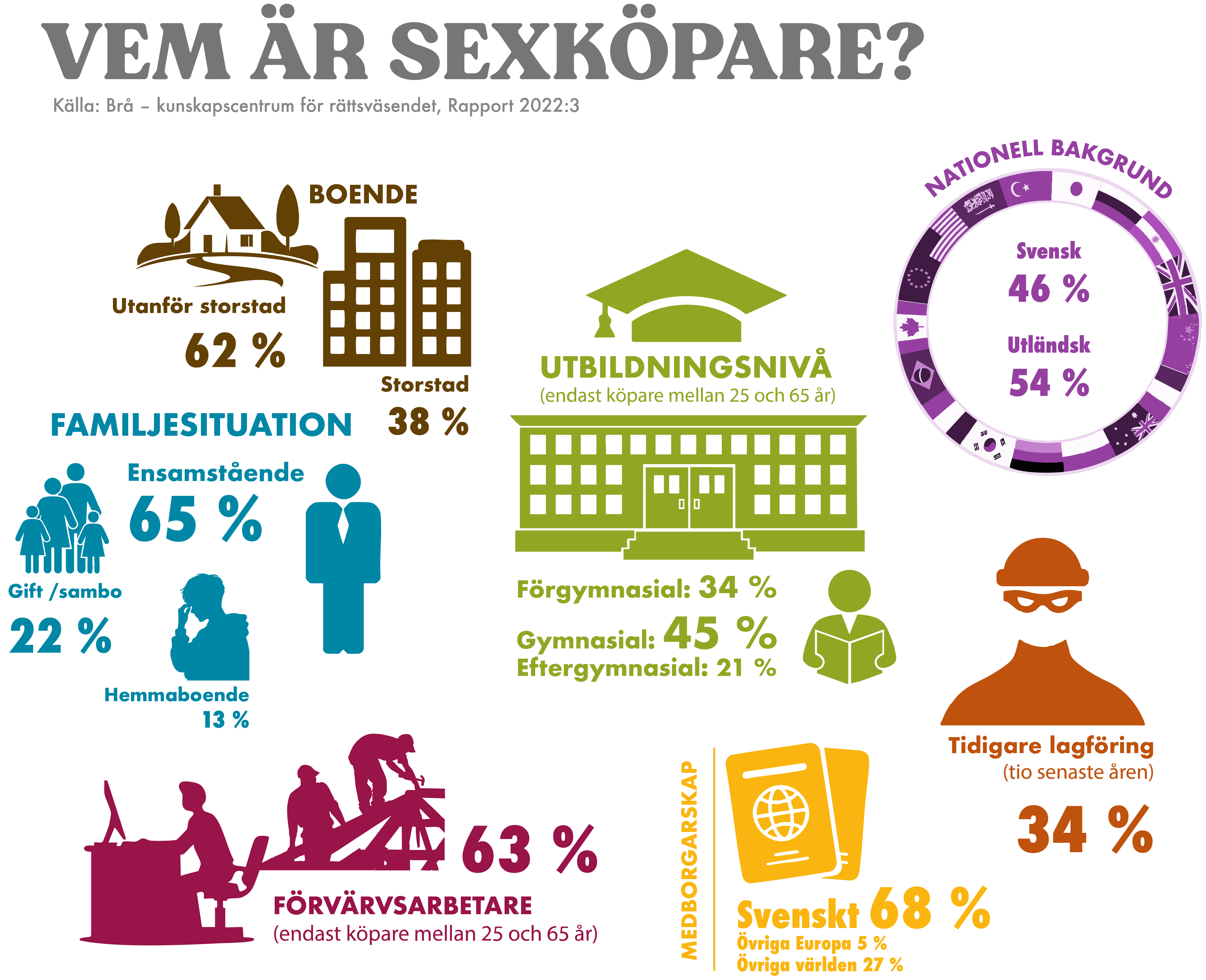

Who are the sex buyers?

- Swedish population studies show that men are the clearly dominant group among sex buyers. In a recent survey commissioned by the Swedish Women's Organizations, approximately 7% of Swedish men stated that they had purchased sex at least once (compared to virtually 0% of Swedish women). Source: Swedish Women's Organizations

- In a national population survey (SRHR2017), the Public Health Agency of Sweden found that a total of 9% of Swedish men have at some point paid for sex – that is, approximately “one in ten men.” Source: Public Health Agency of Sweden.

- It is also the report that later surveys and government reports refer to when they write "one in ten men." Source: GenderEquality Authority

Why do some men buy sex?

As mentioned earlier, Månsson concluded in his research that sex buying is linked to the influence of patriarchy on sexuality. According to Månsson, boys learn to dominate girls in sexual relationships, where the act of domination itself defines traditional male masculinity. As gender equality increases, some men reject women's rights advances and purchase sex to gain access to "the traditional gender order" and to "channel their aggression toward women" (Månsson, 2002, p. 145).

Several recent Swedish interview studies/dissertations have examined why men buy sex.

Two recurring themes are:

Closeness and intimacy as motives

In a thesis from Malmö University (30 interviews), many men describe buying sex as linked to loneliness, a need for closeness, validation or control, rather than "just sexual desire." Shame and attempts to keep purchases secret are also evident. Source: Malmö University

Normalization through pornography/digital environments

Recent Swedish qualitative studies highlight that high pornography consumption, escalating online sexuality, and a habit of purchasing digital intimacy can act as drivers or triggers.

Source: DIVA Portal

How do sex buyers think about risk?

A widely cited study in the British Journal of Criminology (interviews with 30 Swedish sex buyers) shows that men often actively calculate risks:

- Risk of getting caught (police operations, surveillance, digital traces)

- Risk of being scammed/robbed

- Risk that the woman is being coerced

- Risk of losing family/job if it is revealed

They describe strategies for minimizing risk and dealing with stigma in a country where purchasing is prohibited.

How does the Sex Purchase Act affect men's behavior?

There is also research that looks at attitudes among the population and how the Sex Purchase Act affects norms. Among others, the Crime Victim Compensation and Support Authority has studies showing that the ban on purchasing sex in Sweden is linked to an increasingly negative view of sex purchases over time, but that attitudes differ between groups and genders. Source: Crime Victim Compensation and Support Authority

The Gender Equality Authority has recently surveyed Swedish sex purchase websites and analyzed buyer reviews and demand patterns. Among other things, it shows:

- very high traffic of Swedish men on such sites

- a consumption/rating logic that dehumanizes women

- indications that buyers sometimes suspect (or ignore) coercion/human trafficking

Source: SvD.se

This is an important new area of research, as purchases today often begin digitally even when the meeting takes place physically.

Exit program

Talita's exit program is for people who want to leave prostitution, pornography, or other forms of sexual exploitation. The program offers individually tailored support to create security, stability, and new opportunities in life.

Taking the step away from exploitation can be complex and often associated with practical, psychological, and social challenges. That is why we meet each person where they are—without demands, without judgment, and with full respect for the individual's own will and pace.

What does the exit program entail?

The exit program is a comprehensive support package tailored to each participant's needs. It may include:

- Counseling and professional guidance

- Practical support in dealing with authorities

- Help with housing, finances, and daily routines

- Support in matters relating to health, trauma, and self-esteem

- Guidance towards studies, work, or other employment

The goal is to create conditions for a life free from exploitation, with increased independence and optimism about the future.

For whom?

The program is aimed at adults who are involved in, or want to leave, prostitution or pornography—regardless of gender, background, or life situation. Participation is voluntary and free of charge.

Our approach

Talita works from a rights-based and trauma-informed perspective. We believe in the inherent value of every human being and their right to a life of security and dignity. The relationship between participants and staff is based on trust, continuity, and a long-term perspective.

Contact us

If you, or someone you meet in your work, would like to know more about Talita's exit program, you are welcome to contact us. An initial conversation does not commit you to anything—it is simply a step toward exploring the possibilities.

Research

Reports

Alsalem, R. (2024). Prostitution and violence against women and girls: Report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women and girls, its causes and consequences. Human Rights Council, United Nations. A/HRC/56/48. https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/thematic-reports/ahrc5648-prostitution-and-violence-against-women-and-girls-report

CAP International. (2025). Last Girl First! Prostitution at the intersection of sex, race & class-based oppressions. Paris: Coalition for the Abolition of Prostitution International. https://www.editionslibre.org/produit/last-girl-first-a-research-conducted-by-hema-sib-cap-international/

Swedish Ministry of Employment. (2023). Out of vulnerability (SOU 2023:97). Swedish government offices. https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/statens-offentliga-utredningar/2023/12/sou-202397/

Research articles

Averdijk, M., Ribeaud, D., & Eisner, M. (2020). Longitudinal Risk Factors of Selling and Buying Sexual Services Among Youths in Switzerland. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 4(49), 1279–1290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-01571-3

Baker, L. M., Dalla, R. L., & C. Williamson. (2010). Exiting Prostitution: An Integrated Model. Violence Against Women, 16(5), 579-600. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801210367643

Coy, M., Smiley, C., & Tyler, M. (2019). Challenging the “Prostitution Problem”: Dissenting Voices, Sex Buyers, and the Myth of Neutrality in Prostitution Research. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(7), 1931–1935. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1381-6

Cronley, C., Cimino, A. N., Hohn, K., Davis, J., & Madden, E. (2016). Entering Prostitution in Adolescence: History of Youth Homelessness Predicts Earlier Entry. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 25(9), 893–908. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2016.1223246

Farley, M., Cotton, A., Lynne, J., Zumbeck, S., Spiwak, F., Reyes, M. E., Alvarez, D., & U. Sezgin. (2003). Prostitution and Trafficking in Nine Countries: An Update on Violence and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Journal of Trauma Practice, 2(3-4), 33-74. https://doi.org/10.1300/J189v02n03_03

Hanlin, H., Kivisto, A., & Gold, C. (2024). Exploring the link among adverse childhood experiences and commercial sexual exploitation. Child Protection and Practice, 2, Article 100042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chipro.2024.100042

Kaestle, C. E. (2012). Selling and Buying Sex: A Longitudinal Study of Risk and Protective Factors in Adolescence. Prevention Science, 13(3), 314–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-011-0268-8

Klimley, K. E., Carpinteri, A., Van Hasselt, V. B., & Black, R. A. (2018). Commercial sexual exploitation of children: victim characteristics. Journal of Forensic Practice, 20(4), 217–228. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFP-04-2018-0015

Matthews, R. (2015). Female prostitution and victimization: A realist analysis. International Review of Victimology, 21(1), 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269758014547994

Moran, R., & Farley, M. (2019). Consent, Coercion, and Culpability: Is Prostitution Stigmatized Work or an Exploitative and Violent Practice Rooted in Sex, Race, and Class Inequality? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(7), 1947–1953. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1371-8

Månsson, S. A., & Hedin, U. C. (1999). Breaking the Matthew effect - On women leaving prostitution. International Journal of Social Welfare, 8(1), 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2397.00063

Månsson, S.-A. (2017). The history and rationale of Swedish prostitution policies. Dignity: A Journal on Sexual Exploitation and Violence, 2(4). https://doi.org/10.23860/dignity.2017.02.04.01

Ross, C. A., Farley, M., & Schwartz, H. L. (2012). Dissociation among women in prostitution. Prostitution, Trafficking, and Traumatic Stress, 199–212. https://doi.org/10.1300/J189v02n03_11

Searcey, R. (2022). Youth Transitions - Pathways from child to adult sexual exploitation. Loughborough University. https://doi.org/10.17028/rd.lboro.19952930.v1

Strong, C. & C. Hodgson. (2004). Sister Oppressions. Journal of Trauma Practice, 2(3-4), 16-32, https://doi.org/10.1300/J189v02n03_02

Tamarit Sumalla, J. M., Linde García, A., Martín Escribano, P., & Machado García, A. (2024). Cisgender and transgender women who engage in paid sex: involvement and consequences. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 32(July). https://doi.org/10.5944/rdpc.JULIO.2024.42696

Urada, L. A., Rusakova, M., Odinokova, V., Tsuyuki, K., Raj, A., & Silverman, J. G. (2019). Sexual exploitation as a minor, violence, and HIV/STI risk among women trading sex in St. Petersburg and Orenburg, Russia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(22), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224343

Books

Ekman, K. E. (2011). Being and the commodity: prostitution, surrogate motherhood, and the divided human being. Leopard Publishing.

Häggström, S. (2016). Skuggans lag: en spanares kamp mot prostitutionen(The Law of the Shadow: An Investigator's Fight Against Prostitution). HarperCollins Nordic.

Häggström, S. (2018). Nattstad. HarperCollins Nordic.

Moran, R. (2015). Paid for: my journey through prostitution. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Månsson, S.-A. (2018). Prostitution: the actors, the relationships, the surrounding world. Studentlitteratur AB.

Sander, A., & Appelqvist, J. (2024). True stories about the path out of prostitution. HarperCollins Nordic

Statistics

Purchase of sexual services

Source: Reported crimes, Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (BRÅ), published in Statistics Sweden Gender Equality.

Source: Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (BRÅ), published in Statistics Sweden Gender Equality.

Source: Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (BRÅ), published in Statistics Sweden Gender Equality.

Source: Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (BRÅ), published in Statistics Sweden Gender Equality.

The Sex Purchase Act

Source: Swedish Women's Organizations