Introduction

Pimping and human trafficking – modern-day slavery

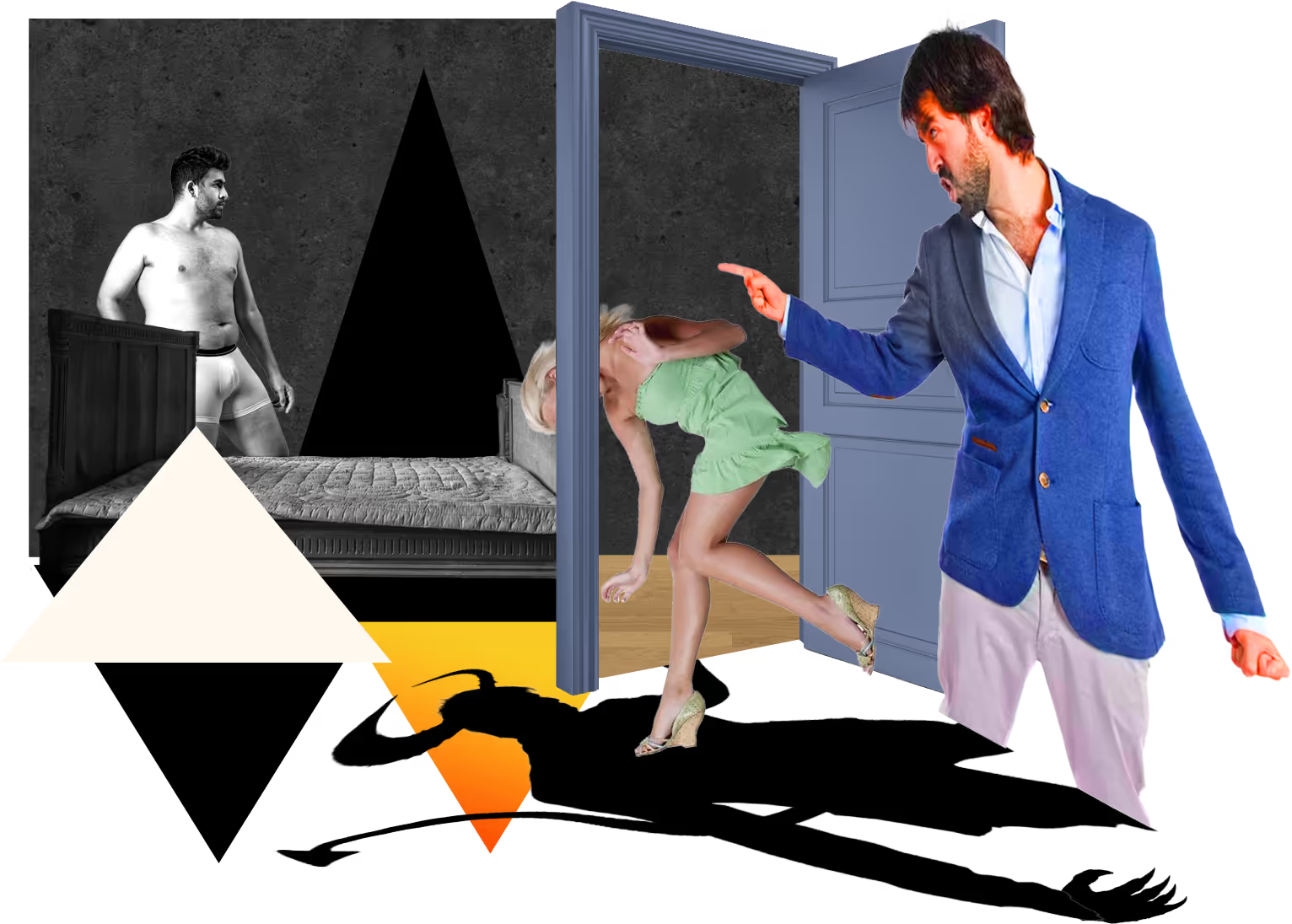

Pimping and human trafficking are closely linked crimes based on the same principle: that people are exploited, controlled, and deprived of their freedom for someone else's gain. Whether the exploitation takes the form of threats, violence, debt bondage, dependency, or psychological manipulation, it is about taking control of another person's body and life.

Today, slavery takes new forms. It is often invisible, normalized, and hidden behind notions of freedom of choice or voluntariness. But behind the façade lies the same reality that has always existed in the history of slavery—people who cannot say no, who lack real alternatives, and who are held back by fear and control.

Understanding the link between pimping and human trafficking is crucial to preventing exploitation, protecting vulnerable people, and strengthening human rights. It is also a necessary part of the work to create a society where no human being is treated as a commodity.

Human trafficking

Two hundred years ago, the transatlantic slave trade was abolished, but today millions of people are slaves in the global human trafficking trade. Human trafficking involves situations where several people, usually in different countries, work together to recruit and then coerce a victim to travel from one place to another, where they are exploited, often in prostitution.

Human trafficking for sexual purposes is driven by demand. The demand to buy another person's body and do whatever one wants with it is the root cause of this horrific reality. Human trafficking is the most profitable form of organized crime, alongside arms and drugs.

Swedish legislation criminalizing human trafficking is found in Chapter 4, Section 1a of the Penal Code and is based on the definition of human trafficking in the supplementary protocol to the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, also known as the Palermo Protocol.

Human trafficking involves transporting a person within or between countries for the purpose of exploitation. The criteria that must be met for it to be considered human trafficking are:

- Intent to exploit (this must have been present from the outset, but intent alone is sufficient; there is no requirement that exploitation must have taken place).

- Trafficking (one or more persons recruiting, transporting, transferring, harboring, or receiving the person to be exploited).

- Improper means (the perpetrator(s) used unlawful coercion, threats, deception, or exploited someone's vulnerable situation to carry out the trade).

Anyone convicted of human trafficking faces a minimum of two and a maximum of ten years in prison. However, to date, no one in Sweden has been sentenced to more than six years in prison for human trafficking. Public statistics indicate that convictions for human trafficking in Sweden are rare and that, in practice, sentences are often well below the maximum. The Gender Equality Authority and other actors have repeatedly shown how rarely convictions are handed down. Source: Gender Equality Authority.

Since the crime involves the perpetrator using "improper means," any consent is irrelevant. This means that it is a case of human trafficking, even if the victim was aware of the prostitution but not the actual conditions. This is a chain crime (recruit-transport-harbor, etc.), but not all links are necessary and there is no requirement that it must occur in a specific order. Different people can also be responsible for different links in this crime.

When it comes to children, the requirement of 'improper means' does not apply. It is sufficient that the trafficking has taken place (recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring, etc.) – it does not matter how it happened, by what means, or whether the child consented or not. All such considerations are irrelevant when it comes to minors.

Human trafficking for sexual purposes was criminalized in Sweden in 2002. A little later, the provision was broadened to also include human trafficking for other types of exploitation, such as begging, criminal activity, organ trafficking, and illegal adoptions. In 2018, a revised section on human trafficking was introduced, and the crime was divided into different degrees of severity. In order to prosecute exploitation that does not meet the requirements for human trafficking, a new crime was created at the same time: human exploitation.

Märta Johansson, associate professor of law at Örebro University, has researched human trafficking, and a recurring theme in her work is that Swedish regulations have high and sometimes unclear requirements, which means that fewer acts are classified as human trafficking than international guidelines would indicate. In "The decade-long metamorphosis of human trafficking: a study of ambiguities and contradictions" (article in Juridisk Tidskrift), she analyzes, among other things, how the crime of human trafficking has changed over time and why it is still difficult to apply. She points out, among other things: ambiguities in the elements of the crime, recurring problems in case law, and the risk that victims fall outside the scope of protection when courts interpret the requirements narrowly.

Find more publications and reports by Märta Johansson here:

https://oru.diva-portal.org

For obvious reasons, it is difficult to produce reliable statistics on the actual number of victims of human trafficking in Sweden, as the crime is largely hidden and involves a high number of unreported cases. The latest overall estimate from the National Criminal Investigation Department was made in 2003 and indicated that approximately 400–600 women and girls could be brought to Sweden annually for prostitution/sexual exploitation. Since then, no new comprehensive national estimate has been published. At the same time, experience from the work of the authorities shows that when resources and targeted efforts increase, more cases are identified, which means that the statistics largely reflect detection and prioritization rather than the actual extent of the crime.

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), human trafficking is a crime area with a high number of unreported cases, making it difficult to determine global totals. Instead, the UN's latest global report shows the trend in identified cases: the number of detected victims increased significantly after the pandemic, and in 2022, around 69,000 identified victims were registered in the countries that report statistics. The same material shows that women and girls continue to make up the majority of detected victims globally.

The ILO, Walk Free, and IOM estimate that approximately 50 million people were living in modern slavery in 2021, a large proportion of whom were in forced labor or forced marriage—phenomena that partly overlap with human trafficking.

Within the EU, girls and women account for over 60% of identified victims of human trafficking. Trafficking in women and children for sexual and other purposes continues to be a structural form of violence against women, and Member States are legally obliged to implement gender-specific protection and support measures. Globally, too, around 60% of identified victims are girls and women. Source: Reuters

Poverty, unemployment, lack of education, discrimination, and other forms of social and economic vulnerability increase the risk of people being recruited and exploited. At the same time, demand is highlighted as a key driver: the market for sexual services, cheap labor, or crime creates incentives for recruiting new victims. In a Swedish court case, for example, it was described how buyers were organized by customer number and contacted by text message or email when new women arrived, illustrating how systematic exploitation can be. Source: Unric.org

Another obvious reason for the existence of human trafficking is that it is simply a profitable business that generates relatively large profits at relatively low risk. It is easier to transport people across borders undetected than drugs and weapons. Women and children can also be sold on several times to increase profits. Some women are lured here by men who promise marriage, money, and a future in Sweden. Others are recruited by an acquaintance or read an advertisement in the newspaper for a job as a nanny or waitress. Some are picked up at strip clubs and brothels. Still others are sold into prostitution by their father or mother. Almost always, the woman is said to owe a debt to the human traffickers—a debt she will never be free of.

That was the case for Michelle. She was said to owe €50,000 to the "madam" who had arranged and paid for her trip to Europe. But it was her father who had made the arrangement with the criminal network for his daughter to go. He was there when Michelle had to undergo a ritual with the blood of sacrificed animals before she was sent away, believing that she would be working as a nanny. Once in Italy, Michelle was locked up in an apartment and forced to have sex with different men several times a day. She tried to escape many times. As punishment, she was raped.

The debt she owed to the human traffickers never decreased. But every time she misbehaved, the debt grew larger. Until the day the police raided the perpetrators. Michelle was said to have run away from her "madam" and as punishment, her father was murdered by the network. Michelle eventually fled from Italy to Sweden and, after a few months, was picked up off the street by outreach workers from a church. She was referred to Talita, and for a couple of years we met with her twice a week for therapy, education, and future planning. Now she has a permanent residence permit in Sweden, a steady job, her own home, and a wonderful family.

The internet is the largest marketplace for all sales of sexual services. There are numerous websites with pictures of girls and women online and detailed information about what "services they can offer" and the price for each "service." Through advertisements on the internet, buyers can also contact booking centers abroad and order a girl or woman. Even before arriving in the destination country, the perpetrators establish increasingly strong control over their victims. This is done through abuse, threats, rape, etc. Once there, control can be maintained partly through external imprisonment, e.g., confinement, threats, and rape, and partly through internal, invisible imprisonment, e.g., through a relationship of dependency, lack of knowledge about laws and practices in the destination country, or threats against family in the home country.

Human trafficking can have serious consequences for the victim. Isolation, threats, humiliation, mental abuse, manipulation, violence, sexual abuse, torture, and forced drug use cause both physical and psychological damage and, in the worst cases, can lead to death. Victims who are given the opportunity to return home also risk being ostracised, as they are considered immoral and bring shame on their family and community. There is then a high risk that they will once again end up in an exploitative situation.

The Swedish National Audit Office is currently reviewing how the Migration Agency, the Police, and the Prosecution Authority are working to combat human trafficking for sexual purposes. The audit will assess whether the work is effective, and the results will be presented in a report scheduled for September 2026.

The background to this is that human trafficking causes great suffering and high social costs, generates large profits for criminals, and is linked to other serious crimes such as money laundering, extortion, and drug trafficking, often via international networks. Despite political priorities and new government mandates, the results of the judicial system are very weak: approximately 600 cases were reported in 2022–2024 without convictions, while three people have been convicted so far this year. Sweden has also received repeated international criticism for its low number of prosecutions and convictions, lack of expertise, low use of temporary residence permits for victims of crime, and inadequate protection of their rights.

Pimping

Pimping is a crime defined in Chapter 6, Section 12 of the Swedish Penal Code, which refers to someone promoting or improperly exploiting another person's temporary sexual relations in exchange for payment. "Promoting" means enabling or facilitating prostitution in some way. This could include, for example:

- Organize customers, premises, or advertisements

- Act as a "driver," "guard," "manager," or intermediary, or

- Operating a business (e.g., club/massage parlor) that is used in practice for prostitution.

The term "unfair financial exploitation" refers to someone taking a share of the proceeds from prostitution in a way that the law considers wrong/exploitative. Typically, this involves:

- take a share of the money

- demand rent/fees linked to prostitution

- live off or systematically profit from others selling sex

Pimping of a normal degree can lead to imprisonment for up to four years. Aggravated pimping (i.e., when the activity is extensive, ruthless, organized, etc.) can, however, lead to a maximum of 10 years in prison.

In everyday language, someone who engages in pimping is usually called a pimp. Pimping is more common in legal texts, but the term has been around for a long time in the Swedish language. As early as the 17th century, pimping began to be regulated, but then with the aim of limiting the spread of sexually transmitted diseases such as syphilis. As a word, however, pimping has a more superstitious origin. Pimping has alluded to people who have been "linked" to the devil through forbidden relationships. Source: SAOB

Sven-Axel Månsson is a Swedish sociologist and professor emeritus in social work (active at Lund, Gothenburg, and Malmö/Malmö University, among others). He is one of Sweden's most long-standing and influential researchers on prostitution, pornography, and sexual exploitation. Månsson co-founded the so-called prostitution project in Malmö in 1977, which became an important early Swedish research and development project on prostitution. Since then, he has published a large number of books, reports, and articles on the conditions of the sex trade and the development of politics.

Through his research and books, Månsson has highlighted the many different individuals and businesses that promote and profit from prostitution in Sweden, including pimps, strip club owners, hotel and restaurant owners, massage parlors, property owners, newspaper publishers, human traffickers, and the pornography industry (Månsson, 1981, pp. 83–106) + (Månsson & Larsson, 1976, pp. 76–80). He has revealed how pimps try to rebrand themselves as legitimate entrepreneurs by using established terms such as "modeling studios" to conceal their pimping activities (Månsson, 2018, p. 34).

According to Månsson, during the recruitment phase, pimps target vulnerable women with low self-esteem, who are easier to manipulate, control, and exploit. Enchanted by the man's "confidence, arrogance, and authority," the woman sees him as "the bearer of the possibility of a different and better life" (Månsson, 1981, p. 155). The pimp's goal is to take advantage of her longing for a romantic relationship and a life together in order to exploit her financially (Månsson, 1981, pp. 136, 150). Promises of marriage, trips abroad, a joint business, etc. convince her that prostitution is to their mutual benefit and for their future together. Through psychological manipulation and brainwashing, "the pimp shapes and controls her will so that it conforms to his own, while blocking her awareness of the process" (Månsson, 2018, p. 193). Månsson was one of the first to draw attention to the so-called lover boy method, which is often used by pimps today.

In the next phase, Månsson explains, the pimp proclaims himself her agent or manager who wants to build up his "star" by taking care of (controlling) her finances, arranging transportation, helping with advertising, etc. He demonstrates his power and dominance over her by monitoring and controlling her movements (Månsson, 1981, p. 173). "Instead of building her up, he begins to break her down. As her self-esteem diminishes, his power over her increases" (Månsson, 1981, p. 173). The pimp's exercise of power shifts from surveillance and control to "siege and occupation," where the woman is locked up (symbolically and/or literally) and isolated from the outside world. "The relationship between the pimp and the prostitute is one of psychological slavery" (Månsson & Larsson, 1976, p. 115), where the threat of physical violence is always present. Månsson explains: "It can be difficult to put into words the fear of another person's cruelty and dangerousness. The more the woman fears the pimp, the greater his power becomes. And at some point in the relationship, she will do anything just to avoid his wrath" (Månsson, 1981, pp. 177–178; 2018, p. 195).

Throughout his writing career, Månsson became increasingly clear about how organized crime was an inherent part of prostitution. As early as 1976, he noted how many pimps were also involved in other criminal activities, such as illegal gambling (Månsson & Larsson, 1976). He also identified a growing international human trafficking business. He believed that the high prevalence of foreign nationalities among pimps, strip club owners, and people in prostitution indicated "an internationalization of the sex trade" (Månsson, 1981, p. 28).

Research

Reports

Swedish Gender Equality Agency. (2025). Work against prostitution and human trafficking in Sweden 2024: Annual report from the National Coordination against Prostitution and Human Trafficking (NSPM) (Report 2025:11). Gothenburg. https://nspm.jamstalldhetsmyndigheten.se/media/ao0jiyip/rapport-2025-11-nspm-arsrapport-2025-04-11.pdf

Swedish Gender Equality Agency. (2025). Regional coordinators' statistics 2024: Statistical data on human trafficking and human exploitation (Report 2025/ALLM 2025/8). Gothenburg. https://nspm.jamstalldhetsmyndigheten.se/media/diaikqgo/statistikrapport-nspm-2025-05-19.pdf

Swedish Police Authority. (2024, December 6). Status Report 25 on Human Trafficking for 2023 (Report). https://polisen.se/siteassets/dokument/manniskohandel/lagesrapport-25-over-manniskohandel-for-2023.pdf/download/?v=3ce1d53fa3587cd6093b3eee858c4354

Research articles

Baird, K., & Connolly, J. (2023). Recruitment and entrapment pathways of minors into sex trafficking in Canada and the United States: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24(1), 189-202, https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380211025241

Franchino-Olsen H. (2021). Vulnerabilities Relevant for Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children/Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking: A Systematic Review of Risk Factors. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 22(1), 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838018821956

Herrington, R. L., & McEachern, P. (2018). “Breaking Her Spirit” Through Objectification, Fragmentation, and Consumption: A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Domestic Sex Trafficking. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma, 27(6), 598–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2017.1420723

Juraschek, E., Legg, A., & Raghavan, C. (2024). The Reconsecration of the Self: A Qualitative Analysis of Sex Trafficking Survivors’ Experience of the Body. Violence Against Women, 30(8), 1842–1865. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778012241239948

Rajaram, S. S., & Tidball, S. (2018). Survivors’ Voices—Complex Needs of Sex Trafficking Survivors in the Midwest. Behavioral Medicine, 44(3), 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2017.1399101

Rocha Jiménez, T., Salazar, M., Boyce, S. C., Brouwer, K. C., Staines Orozco, H., & Silverman, J. G. (2018). “We Were Isolated and We Had to Do Whatever They Said”: Violence and Coercion to Keep Adolescent Girls from Leaving the Sex Trade in Two U.S–Mexico Border Cities. Journal of Human Trafficking, 5(4), 312–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2018.1519753a

Statistics

Source: Crime Prevention Council